Which Letter of the Year Should I Follow?

Before the internet age, news about the Letter of the Year was spread by word of mouth, and rarely extended beyond the confines of the geographical location where the ceremony was held. For example, at the Sociedad el Cristo in Palmira, Cuba, the Letter of the Year has been taken out consistently, year after year, for almost a century, and it was circulated among members of the Sociedad, along with their friends and neighbors, usually those living in Palmira or neighboring towns and villages. It was understood that the information drawn from the Letter of the Year applied to those who identified with that particular community. People living in other places, especially outside Cuba, were rarely aware that the Letter of the Year from El Cristo existed. Instead, if they were involved in Orisha worship, they turned to their own houses to find the Letter of the Year that applied to them.

Since the 1990s, an increasing number of Letters of the Year have appeared on the internet in Spanish and in English, generating debate about which Letter anyone should follow, and why. Does geographical location determine which Letter applies to you? If you aren't associated with any particular Orisha community, which Letter do you follow? Does history and continuity make one Letter more authentic and accurate than another? And, if there are so many Letters of the Year from different places and they all say different things, how meaningful can any of them really be? Is it possible for one Letter of the Year to apply to all humanity?

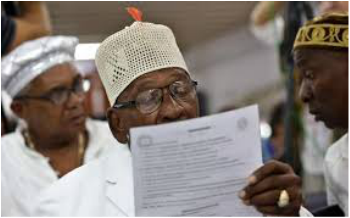

Certainly, it takes a knowledgeable and experienced group of Babalawos to take out the Letter of the Year for a community. The ceremony requires the participation of numerous people trained in the interpretation of Odu, and oversight by a group of religious elders to ensure everything is done correctly. Individuals who have religious and community ties to a specific group will naturally be inclined to follow the advice given by members of their own group. Unfortunately, an increasing number of people initiated into the religion today have no such ties, they have no community, and they turn to the internet to "shop around" for a Letter of the Year that makes sense to them.

What Information Can I Find in the Letter of the Year?

The more important parts of the Letter are the pieces of advice and the proverbs associated with the ruling Odu. These apply to everyone, and can be useful not only in terms of preparing for potential problems but also to avoid hardship and suffering along the way. Much of the advice is based on common sense, but it's particularly relevant to the situations we're going to encounter in the coming year, so it's important to keep it forefront in our minds. The advice always touches on points of health and nutrition, relationships, financial issues, and ethical behavior. We should always pay attention to our health, of course, but in the coming year, we need to be particularly aware of problems related to parts of the body that the Letter of the Year mentions, because those parts are especially vulnerable. The same is true about the rules of ethical behavior. We should always treat others with kindness and courtesy, but some years we need to be more concerned about specific kinds of issues. A warning that says don't offer things you can't fulfill is good general advice for everyone, but when it comes as part of the Letter of the Year, it warns us that not fulfilling promises is a special concern because it has the potential to cause very serious problems at some point during the year.

Other pieces of advice may seem arbitrary and even whimsical, such as "don't whistle" or "don't keep dogs in the house." These are based on patakis, sacred myths, that someone in the religion would probably know and be able to interpret in the proper context, but those outside the religion would dismiss as unimportant. This is where godparents and religious elders can be so important, because they can explain points made in the Letter of the Year that aren't apparent at first glance. For example, the warning about dogs is related to a story about Ogun, where a dog betrayed his presence to an enemy. Dogs are generally loyal and faithful to their masters but they also operate on instinct. Ogun's dog barked and revealed where Ogun was hidden, causing Ogun to suffer at his enemy's hands. Even though it was unintentional, the dog's behavior led to Ogun's downfall. If we have a pet dog who lives in the house with us, we aren't necessarily going to exile the dog to an outdoor kennel for the rest of its life or get rid of the dog. We should, however, be aware that a dog in the house can lead to problems, so we should be vigilant, and we shouldn't expect the dog to behave in ways that are contrary to its instincts and nature. In a more general sense, we have to be concerned about possible unintentional betrayal from someone we trust. The caution against whistling is a reference to Elegua, who whistles to warn us of danger. It's like the story of the little boy who cried wolf; he cried wolf so many times that when a wolf really came along, no one believed him. Elegua is the only one who has the right to whistle, and out of respect for him, we shouldn't whistle in the house. In broader terms, this warning could be taken to mean don't call for help when you don't need it, don't abuse the willingness of others to help you when you're perfectly capable of resolving your own problems. Or, don't encroach on someone else's authority; respect what rightly belongs to someone else.

The proverbs that are associated with the ruling Odu also offer good advice, and call attention to issues that are going to predominate in the coming year. For example, warnings about using time effectively, pacing yourself, knowing when to take charge of a situation or when to delegate to others, and what to expect in your interactions with others helps you navigate the coming year more successfully. The proverbs also offer advice about behavior modification that will make your life go more smoothly. They call attention to specific issues you need to work on, and issues that you're going to face. Being forewarned is being prepared, because it makes you aware of areas where you're most vulnerable.

How Can I Use the Information?

Is the future written in stone? Absolutely not. We come to earth with a destiny, and the challenge is to live out our destiny in the best possible way. The Letter of the Year isn't "fortune telling" but rather an analysis of the energy that surrounds us at a given moment in time. Whether as part of a group or as an individual, we're likely to confront obstacles that are caused by these energies, and we need to be prepared to deal with them. How they impact us depends to a large extent on how we confront them and how we deal with them.

In the coming weeks, we'll look more at the advice and proverbs for 2017, and talk about how the advice pertains to you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed