Iyawó: Newly Initiated in the Religion

A new initiate in Santería stands out

When people begin the week-long initiation process into Santería, they symbolically die and are reborn. Their old life ends, and a new one begins. During that week, in fact, during the entire first year after the initiation ceremony ends, new initiates are called iyawó/ yawó (pronounced: ya-WOH, or ya-BOH). Iyawó is a Lucumí word that's usually translated "bride of the Orichá" (regardless of the sex the initiate), but it's also correct to think of the iyabó as a "novice" in the religion. Both male and female initiates are called iyabó for the first year after initiation, and this one-year period is called the iyaworaje (pronounced: ya-woh-RA-hay). It's a time when the iyabó experiences limitations and prohibitions in terms of behavior, food, dress, contact with other people, and many other aspects of daily life. The year is a period of purification and rejuvination, as the iyabó gets used to interacting with the Orichás in a more intimate way. Traditionally, during the iyaworaje period, new initiates are known in their religious community only as iyabó -not by their given names - in order to ward off any potential osorbo (misfortune) and negative energy sent by ill-intentioned people who want to diminish the iyabó's aché (spiritual strength). The use of the word iyabó instead of their given name also separates them from their old life and ushers them into the new one, where they'll be known in the religious community by a new Lucumí name. To the extent possible, iyabós are expected to live quietly during the year and restrict themselves to activities that they can't be excused from, such as work or school. Those who can't avoid contact with the"outside" world have to take care to avoid situations that are potentially dangerous or disturbing, because as newborns in the religion, iyabós are vulnerable. When religious restrictions conflict with work or school obligations, the iyabó's godmother or godfather helps develop a compromise position that'll allow the iyabó to function in the "real world," while still complying as closely as possible with the demands of the religion. Santería is, above all, a practical religion, and the Orichás don't want someone to lose their job or drop of out school because of religious rules.

Prohibitions for Iyabós

Iyabós dress in white

Most iyabós are immediately recognizable because they dress head to toe in white and cover the head with a scarf or hat. They wear their beaded elekes (necklaces), and when out and about on the street, they may be accompanied by a godparent or elder in the religion, as if they were a young child venturing out with an adult. The white represents purity, peace of mind and spiritual clarity, and the protective behavior of other Santeros/as toward iyabós reflects the belief that they're the bride or groom of the Orichás and must be treated with great care. Iyabós are expected to act with decorum at all times, and respect the prohibitions and taboos that are part of the iyaboraje.

Some prohibitions are generic, such as the need to wear white clothing and avoid make up, perfumes, and jewelry other than the sacred necklaces and bracelets given during initiation. For the first three months after initiation, restrictions are more severe. For example, the iyabó can't sit at the table to eat, but must instead sit on a straw mat on the floor. Iyabós have to eat with a spoon, not a knife and fork, because they're still "babies" in the religion. They have a white dish and white cup reserved for their own use, which must be used every time they eat or drink. They can't look in a mirror or have their pictures taken. They can't drink alcohol. They can't go out at night, be in a large crowd, go swimming in the ocean, or be in the sun at noon. They need to keep their head covered at all times, and avoid shaking hands or accepting anything a person hands them. In general, they should avoid being touched except by close family members or their godparent. The thinking behind these restrictions is that the iyabó is very sensitive to the vibrations of other people and needs to avoid situations where any kind of spiritual contamination might take place. At the same time, iyabós have to avoid situations and settings where the head might become physically or emotionally overheated (such as direct sunlight at noon, or a crowded party with drinking), because the head belongs to the Orichás and it needs to remain cool for the Orichás to bring blessings into the life of the iyabó. After the three month period passes, some restrictions are lifted, but others remain in place for the entire iyaboraje, and some apply to the rest of the iyabó's life.

Some prohibitions are generic, such as the need to wear white clothing and avoid make up, perfumes, and jewelry other than the sacred necklaces and bracelets given during initiation. For the first three months after initiation, restrictions are more severe. For example, the iyabó can't sit at the table to eat, but must instead sit on a straw mat on the floor. Iyabós have to eat with a spoon, not a knife and fork, because they're still "babies" in the religion. They have a white dish and white cup reserved for their own use, which must be used every time they eat or drink. They can't look in a mirror or have their pictures taken. They can't drink alcohol. They can't go out at night, be in a large crowd, go swimming in the ocean, or be in the sun at noon. They need to keep their head covered at all times, and avoid shaking hands or accepting anything a person hands them. In general, they should avoid being touched except by close family members or their godparent. The thinking behind these restrictions is that the iyabó is very sensitive to the vibrations of other people and needs to avoid situations where any kind of spiritual contamination might take place. At the same time, iyabós have to avoid situations and settings where the head might become physically or emotionally overheated (such as direct sunlight at noon, or a crowded party with drinking), because the head belongs to the Orichás and it needs to remain cool for the Orichás to bring blessings into the life of the iyabó. After the three month period passes, some restrictions are lifted, but others remain in place for the entire iyaboraje, and some apply to the rest of the iyabó's life.

Itá and the Fate of the Individual

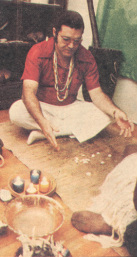

Casting the dilogún

As part of the initiation week, a sacred ceremony called itá takes place. Itá is a lengthy and complex series of consultations with the Orichás who speak through the dilogún (cowrie shells). An oriaté (master of the religion) and several experienced Santeros/as interpret the shells to determine the life path of the new initiate. In Cuba, itá is informally called el juicio final, final judgment, because it gives the initiate, his godparents and members of the religious community a window into the past, present and future of the iyabó. There must be witnesses to the ceremony, so the initiate can always be held accountable by others, and the afeisita (scribe) writes down the information in the iyabó's libreta (notebook), which the iyabó is instructed to consult for the rest of his or her life. Itá offers information about potential health issues, the need for behavior modification, insight into past problems, warnings about future obstacles, and general advice about how to achieve success and fulfillment in life. Any prohibitions that come out in itá will apply to the iyabó as long as he or she's alive. These are related to specific odu (patterns, signs of the shells) that come out during the reading, and are specific to the individual. For example, iyabós might be told that they can't eat a particular kind of food, or they can't wear a particular color of clothing, or they may be advised to avoid certain situations, like a crowded marketplace. While some of these prohibitions may not initially make sense to the iyabó, it's very important to accept them and respect them, because it shows devotion and obedience to the Orichás, which is the main point of the whole process. Iyabós must learn to accept the advice of the Orichás without questioning it, as a way of acknowledging that the human mind can't know everything, and we can't always understand the conditions imposed on us by life.

After the iyaboraje year ends, a special ceremony marks the iyabó's transition to Oloricha (Santero/a) status. Upon completion of all the rituals, he or she can take part in all Santería ceremonies as a priest or priestess of the religion. The iyaboraje is a period that tests the iyabó's faith and dedication to the Orichás. It's a serious commitment to the religion, because "normal" life has to be put on the back burner while the iyabó focuses on spiritual growth and purification. This is one reason why ethical godparents don't rush anyone into initiation, because full scale initiation is a serious business. There's no turning back from it, and it requires enormous sacrifices of time, money, and effort. The initiation ceremony is quite costly (prices vary, depending on the country where initiation takes place) and, in addition, the iyabó has to buy new (white) clothes, towels and sheets, and other necessary items for the year long iyaboraje. Most of the ceremony surrounding initiation is kept secret, so initiates, especially those who haven't grown up in Santero communities, enter into it with little concrete information about what's going to take place inside the igbodú (sacred room). This requires a leap of faith, a willingness to trust the godparent and the Orichás to guide you, and overcoming any fear or doubt you feel about the religion before you enter the initiation room.