Resistance and Change in Cuban Santería

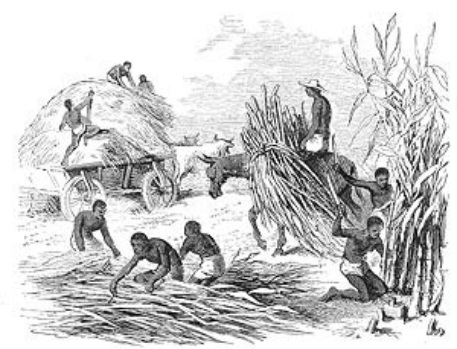

More slaves were needed for sugar plantations

Slavery as an institution arrived in Cuba with the Spanish settlers at the end of the 15th century, but it wasn't until the 19th century that very large numbers of Africans from Yorubaland (today Southwestern Nigeria) came to work the sugar plantations in central Cuba. Between 1820-1860, for example, approximately 275,000 Yoruba-speaking people came to Cuba, where they were known as Lucumí. Other ethnic groups from Africa such as the Kongo/ Bantu people (from what is today Angola) outnumbered the Lucumí in colonial Cuba, but the Lucumí brought with them a very strongly developed culture that they refused to surrender to the dominant Spanish one. Santería, as we know it today, grew out of this spirit of resistance. At the same time, the religion remained alive and flourished because it showed an ability to adapt to new circumstances. Using metaphors borrowed from nature, the Lucumí understood that in the face of a violent storm, the most flexible trees and plants would survive, whereas the ones that refused to bend would be ripped up at the roots and die.

Today, there are substantial differences between the way Yoruba is spoken in modern Africa and the liturgical Lucumí language used in Cuban Santería. Because slaves in Cuba were not generally taught to read and write, their native African languages eventually were transformed into creole variations. The pronunciation of certain Yoruba words and sounds, for example, was influenced by Cuban Spanish; in old handwritten notebooks kept by Santeros/as in Cuba, the spelling of words varies greatly from one text to another and the language no longer follows the grammar or spelling rule of modern Yoruba. During the 19th century, new arrivals from Africa intermixed with people of other ethnic groups and races in Cuba, and through transculturation, the Lucumí worldview began to change slightly. This is one reason anthropologists and folklorists sometimes refer to colonial Cuba as a melting pot; the exchange of ideas and the gradual adaptation to new conditions over time made the Lucumí people different from their Yoruba ancestors and, as a result, the religion known today as Santería is no longer identical to the way the religion is practiced in Africa. In Cuba, people of African origin came together in the barracones (slave dormitories), cabildos (societies), cofradías (brotherhoods) and solares (shared space in urban apartment buildings), they formed bonds through iles (house-temples), ramas (lineages) and religious/ cultural associations. In these shared spaces, they practiced their religion which eventually came to be known as Santeria, or the Regla de Ocha/Ifa.

Today, there are substantial differences between the way Yoruba is spoken in modern Africa and the liturgical Lucumí language used in Cuban Santería. Because slaves in Cuba were not generally taught to read and write, their native African languages eventually were transformed into creole variations. The pronunciation of certain Yoruba words and sounds, for example, was influenced by Cuban Spanish; in old handwritten notebooks kept by Santeros/as in Cuba, the spelling of words varies greatly from one text to another and the language no longer follows the grammar or spelling rule of modern Yoruba. During the 19th century, new arrivals from Africa intermixed with people of other ethnic groups and races in Cuba, and through transculturation, the Lucumí worldview began to change slightly. This is one reason anthropologists and folklorists sometimes refer to colonial Cuba as a melting pot; the exchange of ideas and the gradual adaptation to new conditions over time made the Lucumí people different from their Yoruba ancestors and, as a result, the religion known today as Santería is no longer identical to the way the religion is practiced in Africa. In Cuba, people of African origin came together in the barracones (slave dormitories), cabildos (societies), cofradías (brotherhoods) and solares (shared space in urban apartment buildings), they formed bonds through iles (house-temples), ramas (lineages) and religious/ cultural associations. In these shared spaces, they practiced their religion which eventually came to be known as Santeria, or the Regla de Ocha/Ifa.

Cuban Santería Survived by Adapting to New Circumstances

A sugar plantation in the early 20th century

Some common expressions show the influence of Spanish and Catholicism. For example, in Lucumí the term kariocha refers to the ceremony in which one becomes fully initiated into the religion, but in Cuba it's common for people to talk about it as hacer santo (to make saint). Some people use the name of Catholic saints interchangeably with the names of the Orichás: they call Babalú Ayé San Lázaro, and they call Changó Santa Bárbara. Although this practice is perhaps less common today than it was 50 years ago, it's still a widely accepted idea in Cuba that Orichás can wear the disguise of a Catholic saint. The Lucumí word for priest is Babalocha, and a priestess is called an Iyalocha, but many people in Cuba call them Santeros/as. Whereas the word Santería has been rejected by some practitioners as a holdover from colonial times, others accept it as a word that shows that strength, bravery and determination of the ancestors to keep the religion alive, despite oppressive circumstances. The mixture of Spanish and Lucumí words is an important characteristic of Santería in Cuba and the diaspora.

Over the years, Santería has absorbed some ideas from other races and ethnicities but, rather than surrender to the pressures of the dominant culture, Santería's roots remained firmly planted in the teachings of the ancestors. Today people of all cultures, races and ethnicities are attracted to it as a religion, and it's no longer limited to Cuba or people of African descent. As part of the natural process of transculturation, the religion continues to evolve in modern times, but it can't be removed from its historical and social context without losing some of its authenticity.

Although Santería doesn't have a central figure of authority like a Pope, it does have a loosely connected federation of iles (temple houses) and ramas (lineages), each headed by a Babalocha or Iyalocha of some prestige. They function independently of each other and, while there can be minor differences between them, they are generally in agreement about the need to respect tradition and follow the teachings of the ancestors. Each ilé and rama has the responsibility to make sure that ceremonies are carried out properly and that new initiates receive the proper guidance. For example, though the ceremony known as itá, new initiates get instructions from the Orichás through the dilogún (cowrie shell divination) which will guide them for the rest of their life. Santería encourages practitioners to be very discreet and not share details of their religious experience with outsiders. Historically, Santería survived as a religion by keeping "off the radar screen" of outsiders. Discretion is still an inherent part of the tradition, although the religion no longer has to be hidden from view.

Over the years, Santería has absorbed some ideas from other races and ethnicities but, rather than surrender to the pressures of the dominant culture, Santería's roots remained firmly planted in the teachings of the ancestors. Today people of all cultures, races and ethnicities are attracted to it as a religion, and it's no longer limited to Cuba or people of African descent. As part of the natural process of transculturation, the religion continues to evolve in modern times, but it can't be removed from its historical and social context without losing some of its authenticity.

Although Santería doesn't have a central figure of authority like a Pope, it does have a loosely connected federation of iles (temple houses) and ramas (lineages), each headed by a Babalocha or Iyalocha of some prestige. They function independently of each other and, while there can be minor differences between them, they are generally in agreement about the need to respect tradition and follow the teachings of the ancestors. Each ilé and rama has the responsibility to make sure that ceremonies are carried out properly and that new initiates receive the proper guidance. For example, though the ceremony known as itá, new initiates get instructions from the Orichás through the dilogún (cowrie shell divination) which will guide them for the rest of their life. Santería encourages practitioners to be very discreet and not share details of their religious experience with outsiders. Historically, Santería survived as a religion by keeping "off the radar screen" of outsiders. Discretion is still an inherent part of the tradition, although the religion no longer has to be hidden from view.

How Change Comes About in Santería

Respect the past, look to the future

Santería is, above all, a practical religion that adapts to changing circumstances and conditions. But, change doesn't come about just because human beings desire it. The Orichás have to be in agreement with it, especially Orula, who knows the fate of all human beings, past, present and future. Through divination, Orula and the other Orichás speak through the sacred stories and proverbs of Ocha/Ifa and guide humans in the right direction for survival and adaptation, when needed. For example, with the telephone, air travel and other technological advances, godchildren and godparents can stay in touch with each other across great distances. But, this doesn't take the place of in-person visits and face-to-face consultations. Fundamental practices are still traditional, but not necessarily identical to how they were done in Africa 200 years ago or how they are done in Africa today. Changes take place slowly, and come through collaboration, study and discussion among religious elders who interpret the sacred Odu (signs), patakies (sacred stories) and proverbs to determine what steps need to be taken to keep the religion in tune with modern times. Outside of Cuba and the diaspora, Santería has started to evolve in other ways as people from different ethnicities and backgrounds come into the religion looking for spiritual evolution. Those who are fully initiated in the religion can speak directly with the Orichás using sacred divination tools like the obi (coconut), dilogún (cowrie shells) and epuele (Babalawo's divining chain). If they are knowledgeable about how to read the odu (signs), they can resolve their own problems in direct conversation with the Orichás. This gives the initiated practitioner freedom to practice the religion anywhere.