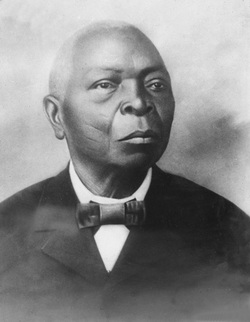

Adesina (Remigio Herrera)

Many people like to start the new year looking at horoscopes or other predictions of what the coming year will bring, but few people outside of the Ocha/ Ifa community are aware of the tradition of drawing out the "letter of the year" (la letra del año) in the hours between the evening of December 31 and the morning of January 1. This is one of the most important and sacred ceremonies for practitioners of the religion, because the Letter of the Year is based on a reading of Odu, the sacred teachings of Orula, the master diviner, who knows the destiny of all mankind, and it is carried out by the most skilled Babalawos in the community who can correctly interpret the meaning of the Odu. Unlike "fortune telling," which usually depends on the individual psychic ability of a reader, the Letter of the Year comes through direct communication with Orula, and requires many years of study on the part of the Babalawos to learn the meanings of the Odu, the proverbs, the offerings, and the ceremonies associated with each sign.

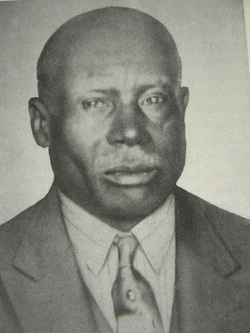

At the end of the 19th century in Cuba, the tradition of drawing out the Letter of the Year became firmly established as a way to provide guidance to practitioners of Ocha/ Ifa during the coming year. Generally, most scholars agree that Remigio Herrera (Adesina) (Obara Meji), a famous Babalawo of African origin living in Havana, was the first to formalize and centralize the ceremony with the assistance of five of his godsons who, in turn, went on to become important Babalawos in their own right: Bernardo Rojas (Irete Untendi), Tata Gaitán (Eulogio Rodríguez, Ogundafun), José Carmen Batista (Ogbeweñe), Marcos García (Ifalola Baba Ejiogbe), and Salvador Montalvo (Okanran Meji). Upon the death of Adesina, Tata Gaitán and Bernardo Rojas took over the ceremony of the Letter of the Year, and Gaitán became especially influential due to his many godsons. In provincial cities such as Palmira in Cienfuegos, established Babalawos like Facundo Sevilla of La Sociedad El Cristo began to draw out the letter of the year for his community, with the assistance of other experienced Babalawos and godsons. The Letter of the Year coming out of El Cristo, although not well known outside of Cuba, has been drawn out without interruption since 1906 and has established the Sevilla branch of Ifa as one of the most respected ones on the island.

At the end of the 19th century in Cuba, the tradition of drawing out the Letter of the Year became firmly established as a way to provide guidance to practitioners of Ocha/ Ifa during the coming year. Generally, most scholars agree that Remigio Herrera (Adesina) (Obara Meji), a famous Babalawo of African origin living in Havana, was the first to formalize and centralize the ceremony with the assistance of five of his godsons who, in turn, went on to become important Babalawos in their own right: Bernardo Rojas (Irete Untendi), Tata Gaitán (Eulogio Rodríguez, Ogundafun), José Carmen Batista (Ogbeweñe), Marcos García (Ifalola Baba Ejiogbe), and Salvador Montalvo (Okanran Meji). Upon the death of Adesina, Tata Gaitán and Bernardo Rojas took over the ceremony of the Letter of the Year, and Gaitán became especially influential due to his many godsons. In provincial cities such as Palmira in Cienfuegos, established Babalawos like Facundo Sevilla of La Sociedad El Cristo began to draw out the letter of the year for his community, with the assistance of other experienced Babalawos and godsons. The Letter of the Year coming out of El Cristo, although not well known outside of Cuba, has been drawn out without interruption since 1906 and has established the Sevilla branch of Ifa as one of the most respected ones on the island.

Tata Gaitán

In the first half of the 20th century, various branches of Ifa practitioners in Havana competed to be recognized as the "official" heirs of Adesina. Jealousy and conflict between powerful Babalawos contributed to instability in drawing out one centralized Letter of the Year for Cuba, and it became commonplace for several Babalawos to draw out Letters of the Year, each one competing for more followers. In 1959, after the Triumph of the Cuban Revolution, the government took a hostile view of any religious activity, including the open practice of Ocha/ Ifa, and this drove many Santeros/as and Babalawos underground. The religion remained alive in Cuba, but it was largely invisible to the public eye until the late 1980s, when the government began to loosen its restrictions on religious practices. During these decades, Cubans leaving the island settled in the United States (especially Southern Florida and the NYC/ New Jersey area), Mexico, Spain, Puerto Rico and other places, creating a Cuban diaspora that introduced Santería and Ifa practices to new communities. As these new religious communities sprang up, Babalawos outside of Cuba began to draw out the Letter of the Year for their own followers. Today, it's common to find Letters of the Year done by Ifa priests in Florida, California, Mexico, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, and many other places where Cubans have settled. Because Santería is now an international religion, the Letters of the Year have also become international.

In Havana in 1986, a large group of independent Babalawos joined forces to draw out the Letter of the Year in a centralized way again; they became known as the Miguel Febles Padrón Commission (CMFP). Since then, they have met each year to draw out the letter, bringing together 800 or more Babalawos some years to take part in the ceremony. Although not officially recognized by the Cuban government, the Letter of the Year done by the CMFP is one of the most famous ones both inside and outside of Cuba. Typically it's translated into English and other languages and circulates all over the world via internet. In the United States, the CMFP Letter of the Year is often the preferred one for chiefly political reasons. Since the CMFP is not associated with the current Cuban government, it has no "communist" connotations. By contrast, the Letter of the Year done by the ACY (Yoruba Cultural Association) is supported by the Cuban government and given "official" status in Cuba. It appears in the newspaper and is broadcast on radio and it circulates widely on the island. Both groups are based in Havana, but the tension between them means that Babalawos from one group don't associate with those of the other groups. In Cuba, both have adherents, but outside of Cuba, especially in South Florida and among the Cuban-American population, the Letter of the Year by the ACY is often rejected as "phony" because people believe it props up the ideology of the Cuban government.

In Havana in 1986, a large group of independent Babalawos joined forces to draw out the Letter of the Year in a centralized way again; they became known as the Miguel Febles Padrón Commission (CMFP). Since then, they have met each year to draw out the letter, bringing together 800 or more Babalawos some years to take part in the ceremony. Although not officially recognized by the Cuban government, the Letter of the Year done by the CMFP is one of the most famous ones both inside and outside of Cuba. Typically it's translated into English and other languages and circulates all over the world via internet. In the United States, the CMFP Letter of the Year is often the preferred one for chiefly political reasons. Since the CMFP is not associated with the current Cuban government, it has no "communist" connotations. By contrast, the Letter of the Year done by the ACY (Yoruba Cultural Association) is supported by the Cuban government and given "official" status in Cuba. It appears in the newspaper and is broadcast on radio and it circulates widely on the island. Both groups are based in Havana, but the tension between them means that Babalawos from one group don't associate with those of the other groups. In Cuba, both have adherents, but outside of Cuba, especially in South Florida and among the Cuban-American population, the Letter of the Year by the ACY is often rejected as "phony" because people believe it props up the ideology of the Cuban government.

Babalawo reading Odu

So, what kind of information is in a typical Letter of the Year? You can find some on the Internet and study them to get a better idea of what they look like, but generally they are difficult to interpret unless one has some knowledge of Lucumí traditions, words, and ceremonies. The Odu and the proverbs linked to Odu are hermetic and vague, unless one has formally studied Odu and can tease out the correct meaning. For this reason, most people consult with their Godparent to go over the Letter of the Year, to be sure that they understand it properly.

First, there will be a governing Odu for the year, which sets the tone and establishes the main themes to be addressed that year. It can come with iré (blessings) or osobo (misfortune), and in the case of osorbo, there's an indication of what kind to expect (sickness, death, war, loss, etc.) and where it will come from. There will be one Oricha who governs, and another Oricha who accompanies the first one. During the year, the energy of these two Orichas will be very important, and people will need to address petitions to them to resolve their problems and enjoy more blessings. The Letter of the Year outlines some of the major ebo (offerings) for the year, offers proverbs that illustrate aspects of the Odu, and makes specific recommendations about what to do or what to avoid to have good health, prosperity, good relationships, and avoid problems. Some of these address worldwide problems, such as food shortages, epidemics, atmospheric or climatic changes, and war. Others address individual problems such as health issues, family problems, or problems in a relationship. The Letter of the Year uses language that is somewhat vague and open to interpretation; you'll never find specific mention of people or places by name, so any one who claims that the Letter of the Year predicts the death of a certain individual or the fall of a certain government reflects the personal opinion of the speaker, not the actual Letter of the Year. The Letter of the Year is always open to interpretation, and sometimes it requires deep knowledge of Odu to understand all the ramifications.

While everyone hopes the new year will come with iré (blessings), it's important to remember as we await the new Letter of the Year, that osorbo (misfortune) gives us an opportunity to change, grow, develop, build strength and courage, and deal with adversity through our own good character. Ocha/ Ifa teaches us that we can modify bad luck and misfortune through our own good work, good thoughts, and good behavior.

First, there will be a governing Odu for the year, which sets the tone and establishes the main themes to be addressed that year. It can come with iré (blessings) or osobo (misfortune), and in the case of osorbo, there's an indication of what kind to expect (sickness, death, war, loss, etc.) and where it will come from. There will be one Oricha who governs, and another Oricha who accompanies the first one. During the year, the energy of these two Orichas will be very important, and people will need to address petitions to them to resolve their problems and enjoy more blessings. The Letter of the Year outlines some of the major ebo (offerings) for the year, offers proverbs that illustrate aspects of the Odu, and makes specific recommendations about what to do or what to avoid to have good health, prosperity, good relationships, and avoid problems. Some of these address worldwide problems, such as food shortages, epidemics, atmospheric or climatic changes, and war. Others address individual problems such as health issues, family problems, or problems in a relationship. The Letter of the Year uses language that is somewhat vague and open to interpretation; you'll never find specific mention of people or places by name, so any one who claims that the Letter of the Year predicts the death of a certain individual or the fall of a certain government reflects the personal opinion of the speaker, not the actual Letter of the Year. The Letter of the Year is always open to interpretation, and sometimes it requires deep knowledge of Odu to understand all the ramifications.

While everyone hopes the new year will come with iré (blessings), it's important to remember as we await the new Letter of the Year, that osorbo (misfortune) gives us an opportunity to change, grow, develop, build strength and courage, and deal with adversity through our own good character. Ocha/ Ifa teaches us that we can modify bad luck and misfortune through our own good work, good thoughts, and good behavior.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed