Take Santería for example. Santería is an established religion with roots in Western Africa. Does that mean that white people shouldn't practice it? No, absolutely not. Santería doesn't exclude anyone on the base of race or ethnicity. Santería has roots in Cuba, where it was originally practiced in black communities, but that doesn't mean that only Afro-Cubans have the right to be part of the religion. Many Santería practitioners do speak Spanish because of their ancestral ties to the Hispanic Caribbean, but Santería isn't confined to one geographic area, one language or even one culture anymore. It's truly a global religion. But, it is still a religion. That means it has sacred ceremonies, liturgical language, and rules about how things need to be done. The rules aren't invented by individuals, but come down from the ancestors. They reflect a desire and a need to adhere to tradition, as a way of honoring the ancestors and all they did to keep the religion alive, sometimes in very harsh circumstances and against fierce pressure to let it go. The belief system that's the foundation of Santería is ancient and sacred. The Lucumí people believe that it was given to them by God. They feel a responsibility to keep their traditions sacred because of their close connection to the ancestors and to the Orichás, who are God's messengers on earth. This is one reason that the religion is based on initiation. Initiation rituals are complex, costly, and reserved only for those who have been chosen by the Orichás through divination to enter the religion in a formal way. Other religions have rituals that bring individuals into the church, such as Baptism, Confirmation, and Communion, and marriage and funeral rites. But most westerners these days aren't really familiar with initiatory religions that require such complicated (and to some degree) secret ceremonies.

In Latino communities in the USA, that same way of thinking applies, and people practice the religion on different levels, under the supervision and with the guidance of an established (and, hopefully, reputable) Santero/a. People who really understand Santería from a cultural perspective know that it's not a do-it-yourself kind of religion. Whether the individual truly believes in the tenets of Santería or not, most people who have been raised in communities where Santería is actively practiced by people they know and trust understand that you don't play around with the Orichás, Santería is a religion and it must be respected.

True, Santería is described as a syncretic religion, and has borrowed elements from other sources like Catholicism over the years. But these were organic changes brought about over time by a community of people. It wasn't an individual choice, but a natural process geared toward the survival of an established religious system in a new setting.

People who approach Santería from the outside often come at it with a totally different idea of what it is, what it can do for them, or how they can make it part of their lives. They're attracted by the exotic, magical and mystical qualities they associate with non-European religious traditions. They embrace superficial (and often incorrect) notions about what Santería is, and they declare that they practice Santería, without understanding the underlying metaphysical foundation, the history, philosphy and culture of the religion. They think they can appropriate the aspects they like about Santería, ignore or change the aspects they don't like or don't understand.

But, sorry to sound harsh here, the person who reads about Santería on the internet or in books, and who tries to bypass the steps that will lead him into the religion in the proper way, is only fooling himself if he thinks he's practicing Santería. Santería requires community. The community must be led by people who are initiated in the religion, understand the traditions, and are committed to seeing that the traditions are kept sacred. Santería doesn't permit shortcuts. Individuals can't pick it up like a new hobby and expect to connect to it in any meaningful way. And people certainly can't pick and choose the parts they like, throwing the rest way, and claim that they are practitioners of the religion. The religion requires acceptance of the traditions, and respect for them.

These are aspects of the religion that are hard for some people to grasp in our modern take-charge world. If you're used to being in charge of everything and making all your own choices and decisions, if you want to be the one who calls all the shots and does everything the way you want, if you think you're entitled to reject the teachings of religious elders if their teachings don't gel with your established worldview, you're going to have trouble with Santería. The religion doesn't call for mindless obedience, but it does require you to go with the established program. It requires you to follow the lead of others, to respect the traditions of a community, to let religious elders guide you.

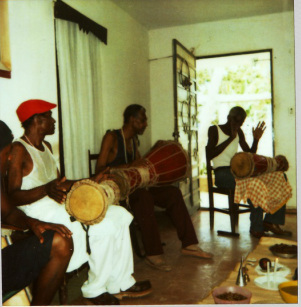

What's the best thing to do if you want to be involved in a Santería community and you don't know how to find one? Depending on where you live, this can be easy or hard. Try looking for music festivals that include African drumming and dancing. See if there are botánicas in your city, and check them out. If there's a Puerto Rican, Cuban or Dominican community in your city, go to events they sponsor, check out lectures, films, or workshops that focus on Afro-Caribbean culture. Ask around. Above all, don't be in a hurry. Don't jump into anything without knowing who and what you're dealing with. If your desire to be a part of Orichá worship is genuine, the Orichás will guide you where you need to go, and put you in contact with people you need to meet. It may take time, but it will happen. In the meantime, it's good to educate yourself, using reputable sources of information like this website, to understand the principles of the religion, and to know what you can expect from involvement in the religion, if you decide to go down that path.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed