Santeros can be victims of hate crimes

Look up Santería in the news using any search engine and you'll find two kinds of news: one focuses on crimes attributed to people who practice Santería, and the other kind focuses on practitioners of Santería as victims of hate crimes. One story that appeared last summer in the news was about the persecution of Carlos Valdés, an Oriate (high priest of Santería) living in West Kendall, Florida. A stalker threatened Valdés, his family and his godchildren in the religion with violence, demanding that they stop practicing Santería or he would kill them. The stalker, later identified as Cuban American Kellyd Rodríguez, open fired on Valdes's home, leaving bullet holes in the walls. Rodríguez had terrorized Valdés's family for four years; his actions included rock throwing, drive by shootings, death threats, and phone calls to Valdés's daughters' school, in which he informed them (incorrectly) that their parents had been killed in an accident. Rodríguez was eventually arrested and charged with stalking, but Valdés is pushing for him to be charged with a hate crime. If Valdés is successful in getting the getting the charges changed, it will be the first official hate crime case involving anti-Santería sentiments in the US.

As background to the Valdés case, reporters quoted Oba Ernesto Pichardo, who went to the Supreme Court in 1993 to defend Santería under the US Constitution's guarantee of religious freedom. (Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah) The Court's decision supported Pichardo's claim that Santería is a religion and, thus, legally deserves to be treated as one. Nevertheless, many people ignore this benchmark decision and continue to harrass practitioners of Santería for their religious beliefs. Pichardo remarked, "I've had crucifixes thrown through my windows and a woman try to burn my church down. So many people in Miami still don't realize that a santero in his home has the exact same legal rights as a Catholic priest in his church or a Jewish rabbi in his synagogue." (www.miaminewtimes.com/2011-08-18/news/santeria-stalker/)

Pichardo hits the nail on the head when he says that people don't recognize the legal rights of Santeros to practice their religion. Religious persecution isn't new by any means, and certainly at different points in time different religions have experienced hate crimes. Santería isn't unique in that way, but what always catches my attention is the supposition by mainstream society that Santería isn't a religion at all and, therefore, persecution of its practitioners isn't a hate crime.

As background to the Valdés case, reporters quoted Oba Ernesto Pichardo, who went to the Supreme Court in 1993 to defend Santería under the US Constitution's guarantee of religious freedom. (Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah) The Court's decision supported Pichardo's claim that Santería is a religion and, thus, legally deserves to be treated as one. Nevertheless, many people ignore this benchmark decision and continue to harrass practitioners of Santería for their religious beliefs. Pichardo remarked, "I've had crucifixes thrown through my windows and a woman try to burn my church down. So many people in Miami still don't realize that a santero in his home has the exact same legal rights as a Catholic priest in his church or a Jewish rabbi in his synagogue." (www.miaminewtimes.com/2011-08-18/news/santeria-stalker/)

Pichardo hits the nail on the head when he says that people don't recognize the legal rights of Santeros to practice their religion. Religious persecution isn't new by any means, and certainly at different points in time different religions have experienced hate crimes. Santería isn't unique in that way, but what always catches my attention is the supposition by mainstream society that Santería isn't a religion at all and, therefore, persecution of its practitioners isn't a hate crime.

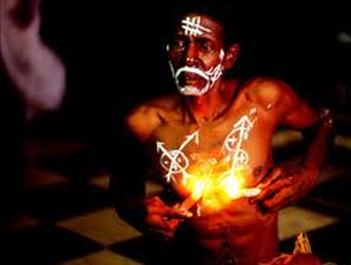

Palo Monte and Santería are not the same

I may be wrong, but I think when someone bombs a synagogue or a mosque, they aren't challenging the idea that Judaism or Islam is a religion. They're expressing hatred for people who practice those faiths. Why isn't someone who does the same thing to a Santero's home automatically charged with a hate crime? Why does the charge need to be discussed? It should be automatic, if Santería is protected as a religion by US law, as other religions are. It's always wrong to commit hate crimes, but it's doubly wrong to direct violent actions toward people whose belief system you don't recognize as a legitimate religion. You're hurting them twice, by doing violence to them, and by denying that their belief system constitutes a valid religion. The difference between a hate crime and a case of stalking is that a hate crime has an ideological basis, not a personal one. Rodríguez targetted Valdés not an an individual he had a problem with, but as a symbol of a religion he found unacceptable.

Another story in the news reports that a 4 year old girl in Roswell Georgia was cut with a straight-edge razor as part of a Santería ceremony. This kind of story is typical of what we find in the media when Santería is linked to the abuse of people and animals. The reporter consulted a practitioner of Santería for clarification but somehow managed to miss the main point: Santería rituals don't involve the cutting of children. Period. A friend of the family identified as a practitioner of Santería claims that "the ritual [of cutting] is a form of self-sacrifice to the saints they worship." Hmm... that's not exactly true... Who misunderstood what was being said here? The friend (who doesn't know what Santería is) or the reporter (who is equally misinformed)? The reporter explained that the ceremony of cutting is called "Paulo," which would be laughable if it were not for the seriousness of the accusation. Presumably, the reporter means "Palo," short for Palo Monte or the Regla de Congo, which is a West African religion practiced in the Caribbean diaspora, but not the same as Santería (Regla de Ocha). I'm not a specialist in Palo Monte, but I know that it's not common for a 4 year old girl to be "scratched," as practitioners call it, unless there's a very serious reason for it. In the article, there's no discussion of why the ceremony was carried out or what motivated her parents to initiate her into the religion at that early age. Instead, the articles ends by stating that Georgia police are looking into the case and may charge the parents with child abuse.

(http://abclocal.go.com/kabc/storysection=news/national_world&id=8534743)

Once again, between the lines of this article is the implication that Santería (and Palo Monte) are not real religions, and parents who practice these faiths don't have the right to make decisions about the religious upbringing of their children. Jewish law requires male children to be circumcised, which is also an act of ritualized "cutting" of children's bodies. Why is it different from the "rayamiento" used in Palo Monte? I'm not promoting the abuse of children, and certainly not a fan of cutting children's bodies. But every religion has ceremonies that involve the body in one way or another, from baptism to funeral rites. When it an action considered "child abuse," and when it is considered a legitimate religious ritual? This is a question the news articles never ask.

Below you can see Carlos Valdés as a guest on a Miami television show. The video is in Spanish.

Another story in the news reports that a 4 year old girl in Roswell Georgia was cut with a straight-edge razor as part of a Santería ceremony. This kind of story is typical of what we find in the media when Santería is linked to the abuse of people and animals. The reporter consulted a practitioner of Santería for clarification but somehow managed to miss the main point: Santería rituals don't involve the cutting of children. Period. A friend of the family identified as a practitioner of Santería claims that "the ritual [of cutting] is a form of self-sacrifice to the saints they worship." Hmm... that's not exactly true... Who misunderstood what was being said here? The friend (who doesn't know what Santería is) or the reporter (who is equally misinformed)? The reporter explained that the ceremony of cutting is called "Paulo," which would be laughable if it were not for the seriousness of the accusation. Presumably, the reporter means "Palo," short for Palo Monte or the Regla de Congo, which is a West African religion practiced in the Caribbean diaspora, but not the same as Santería (Regla de Ocha). I'm not a specialist in Palo Monte, but I know that it's not common for a 4 year old girl to be "scratched," as practitioners call it, unless there's a very serious reason for it. In the article, there's no discussion of why the ceremony was carried out or what motivated her parents to initiate her into the religion at that early age. Instead, the articles ends by stating that Georgia police are looking into the case and may charge the parents with child abuse.

(http://abclocal.go.com/kabc/storysection=news/national_world&id=8534743)

Once again, between the lines of this article is the implication that Santería (and Palo Monte) are not real religions, and parents who practice these faiths don't have the right to make decisions about the religious upbringing of their children. Jewish law requires male children to be circumcised, which is also an act of ritualized "cutting" of children's bodies. Why is it different from the "rayamiento" used in Palo Monte? I'm not promoting the abuse of children, and certainly not a fan of cutting children's bodies. But every religion has ceremonies that involve the body in one way or another, from baptism to funeral rites. When it an action considered "child abuse," and when it is considered a legitimate religious ritual? This is a question the news articles never ask.

Below you can see Carlos Valdés as a guest on a Miami television show. The video is in Spanish.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed