Gossip and negative conversations create osogbo

Tiya-tiya spreads through gossip

Tiya-tiya spreads through gossip I agree that we shouldn't talk about osogbo too much, but in recent months I've been reflecting on how the world around us seems plagued by a kind of osogbo we call tiya-tiya. This concerns me because once tiya-tiya exists, it can self-perpetuate and spread like a virus. We end up with a spiritual pandemic.

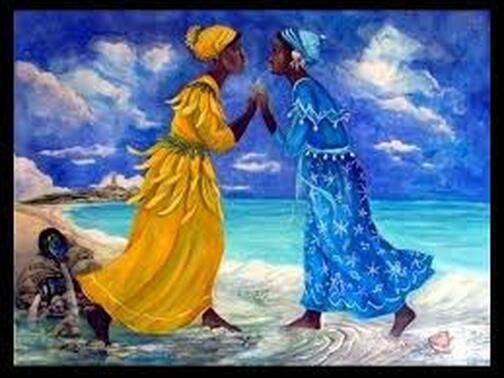

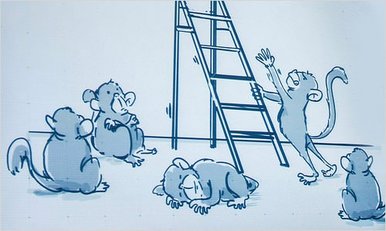

Tiya-tiya is associated with gossip, negative conversations, fighting with words. It splits people into factions, turns people against each other, and sows division that tears apart society. It can happen at any level of human exchange, between family members and friends, work colleagues, neighbors, political parties, religious groups. It's not simply complaining about bad conditions or expressing frustration with circumstances beyond our control. Who hasn't complained about covid-19 in the past few months? Who isn't frustrated by what we see and read in the news? Tiya-tiya is more harmful and more insidious than just venting or expressing outrage. It's aimed against another person or group of people with the intention of diminishing them, hurting them, causing them problems, or ruining their reputation. It's done on purpose, and spread in ways that will ensure it does damage.

Social media can be a breeding ground for tiya-tiya

Social media has played a part in the development of an argument culture because with twitter, instagram, facebook and other platforms, people can reach and influence a wide audience. We've become used to seeing politicians attack each other verbally on television and the internet. We see celebrity squabbles in magazines and on entertainment shows. Reality tv has made arguing and fighting a spectator sport. We internalize this kind of behavior as acceptable, even when we don't like it. When we see it transferred to our own immediate life and world, it becomes intensely personal and can trigger emotional responses. We can internalize the negative conversations, and then spread them to others through our own posts, messages, texts, and conversations. Tiya-tiya can take on a life of its own and invade the lives of people who are not even involved in the event that triggered the trauma in the original post.

How does tiya-tiya impede us?

Negative conversation chases people away

Negative conversation chases people away I don't know how to rid the world of tiya-tiya but, personally, I’m going to do what I can to keep tiya-tiya out of my life. I hope others will do the same. These are turbulent times we're going through, and I pray that everyone comes through them with minimum harm and trauma. May the blessings of Olodumare and the Orishas guide your way and clear osogbo from your path.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed